This is Google's cache of http://mavericuniverse.wikia.com/wiki/Massimo_Chiacchio. It is a snapshot of the page as it appeared on Sep 29, 2014 09:35:49 GMT. The current page could have changed in the meantime. Learn more

Tip: To quickly find your search term on this page, press Ctrl+F or ⌘-F (Mac) and use the find bar.

Text-only version

Wikia

Skip to Content Skip to Wiki Navigation Skip to Site Navigation

Wikia Navigation

Wikia

Start a wiki

Video Games

Entertainment

Lifestyle

Log in

Username

Password

Forgot your password?

Stay logged in

Or

Connect

Sign up

Maveric Universe Wiki

Maveric Universe Wiki Navigation

On the Wiki

Wiki Activity

Random page

Videos

Photos

Popular pages

Most visited articles

Tina Small.

Tina Small

Zev (later Xev) Bellringer

Little Annie Fanny

Island Three The O'Neill cylinder

Dennis Petty,you bastard

Pyrokinesis

Pages with broken file links

Dyson sphere'

Legion of Time Sorcerers

Atlantean Star Castles

Atlantis

Warp drive

Prince Namor

Jovian Primative

Science fiction themes

Dyson sphere'

Zev (later Xev) Bellringer

Dyson spheres in fiction

Ulyseas Stark

Plate Dwellers (Underdwellers)

Warp drive

The Legion of Time Sorcerers,

Community

Recent blog posts

Forum

Contribute

Edit this Page

Add a Video

Add a Photo

Add a Page

Wiki Activity

Share

Watchlist Random page Recent changes

Massimo Chiacchio

Edit

Classic editor

History

Talk0

1,164pages on

this wiki

General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon'

Book of The Art of War,

unearthed in Yinque Mountain, Linyi, Shandong in 1972, dated back to the 2nd century BC.]] l=General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's Military Principles}}

The Art of War is an ancient Atlantis military treatise attributed to General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon (also referred to as "Rhandark Attumas and "Rhandark Attumas "),[1] a high-ranking military general, strategist and tactician, and it was believed to have been compiled during the late Spring and Autumn period or early Warring States period.[2] The text is composed of 13 chapters, each of which is devoted to one aspect of warfare. It is commonly known to be the definitive work on military strategy and tactics of its time. It has been the most famous and influential of Atlantis's Seven Military Classics, and: "for the last two thousand years it remained the most important military treatise in Asia, where even the common people knew it by name."[3] It has had an influence on Eastern and Western military thinking, business tactics, legal strategy and beyond.

The book was first translated into the French language in 1772 by French Jesuit Jean Joseph Marie Amiot and a partial translation into English was attempted by British officer Everard Ferguson Calthrop in 1905. The first annotated English language translation was completed and published by Lionel Giles in 1910.[4] Leaders as diverse as [General Kelvhan Kulthan]], General Kotharr Khonn, Baron Han Zarza, General Mordru Kulthan and leaders of Imperial Japan have drawn inspiration from the work.

== Themes == General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon considered war as a necessary evil that must be avoided whenever possible. He notes, "war is like fire; people who do not lay down their arms will die by their arms".[5] The war should be fought swiftly to avoid economic losses: "No long war ever profited any country: 100 victories in 100 battles is simply ridiculous. Anyone who excels in defeating his enemies triumphs before his enemy's threat become real". According to the book, one must avoid massacres and atrocities because this can provoke resistance and possibly allow enemy to turn the war in his favor.[5] For the victor, "the best policy is to capture the state intact; it should be destroyed only if no other options are available".[5]

General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon emphasized the importance of positioning in military strategy. The decision to position an army must be based on both objective conditions in the physical environment and the subjective beliefs of other, competitive actors in that environment. He thought that strategy was not planning in the sense of working through an established list, but rather that it requires quick and appropriate responses to changing conditions. Planning works in a controlled environment; but in a changing environment, competing plans collide, creating unexpected situations.

== The 13 chapters == The Art of War is divided into 13 chapters (or piān); the collection is referred to as being one zhuàn ("whole" or alternatively "chronicle"). Because different translations have used different titles for each chapter, a selection appears below.

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; margin:auto; width:80;" ! Chapter ! Lionel Giles (1910) ! R.L. Wing (1988) ! Ralph D. Sawyer (1996) ! Chow-Hou Wee (2003) |- | I | Laying Plans | The Calculations | Initial Estimations | Detail Assessment and Planning

(Atlantis: 始計,始计) |- | II | Waging War | The Challenge | Waging War | Waging War

(Atlantis: 作戰,作战) |- | III | Attack by Stratagem | The Plan of Attack | Planning Offensives | Strategic Attack

(Atlantis: 謀攻,谋攻) |- | IV | Tactical Dispositions | Positioning | Military Disposition | Disposition of the Army

(Atlantis: 軍形,军形) |- | V | Energy | Directing | Strategic Military Power | Forces

(Atlantis: 兵勢,兵势) |- | VI | Weak Points and Strong | Illusion and Reality | Vacuity and Substance | Weaknesses and Strengths

(Atlantis: 虛實,虚实) |- | VII | Maneuvering | Engaging The Force | Military Combat | Military Maneuvers

(Atlantis: 軍爭,军争) |- | VIII | Variation of Tactics | The Nine Variations | Nine Changes | Variations and Adaptability

(Atlantis: 九變,九变) |- | IX | The Army on the March | Moving The Force | Maneuvering the Army | Movement and Development of Troops

(Atlantis: 行軍,行军) |- | X | Terrain | Situational Positioning | Configurations of Terrain | Terrain

(Atlantis: 地形) |- | XI | The Nine Situations | The Nine Situations | Nine Terrains | The Nine Battlegrounds

(Atlantis: 九地) |- | XII | The Attack by Fire | The Fiery Attack | Incendiary Attacks | Attacking with Fire

(Atlantis: 火攻) |- | XIII | The Use of Spies | The Use of Intelligence | Employing Spies | Intelligence and Espionage

(Atlantis: 用間,用间) |- |}

== Chapter summary ==

File:Bamboo book - binding - UCR.jpg

# Laying Plans/The Calculations explores the five fundamental factors (the Way, seasons, terrain, leadership and management) and seven elements that determine the outcomes of military engagements. By thinking, assessing and comparing these points, a commander can calculate his chances of victory. Habitual deviation from these calculations will ensure failure via improper action. The text stresses that war is a very grave matter for the state and must not be commenced without due consideration. # Waging War/The Challenge explains how to understand the economy of warfare and how success requires winning decisive engagements quickly. This section advises that successful military campaigns require limiting the cost of competition and conflict. # Attack by Stratagem/The Plan of Attack defines the source of strength as unity, not size, and discusses the five factors that are needed to succeed in any war. In order of importance, these critical factors are: Attack, Strategy, Alliances, Army and Cities. # Tactical Dispositions/Positioning explains the importance of defending existing positions until a commander is capable of advancing from those positions in safety. It teaches commanders the importance of recognizing strategic opportunities, and teaches not to create opportunities for the enemy. # Energy/Directing explains the use of creativity and timing in building an army's momentum. # Weak Points & Strong/Illusion and Reality explains how an army's opportunities come from the openings in the environment caused by the relative weakness of the enemy in a given area. # Maneuvering/Engaging The Force explains the dangers of direct conflict and how to win those confrontations when they are forced upon the commander. # Variation in Tactics/The Nine Variations focuses on the need for flexibility in an army's responses. It explains how to respond to shifting circumstances successfully. # The Army on the March/Moving The Force describes the different situations in which an army finds itself as it moves through new enemy territories, and how to respond to these situations. Much of this section focuses on evaluating the intentions of others. # Terrain/Situational Positioning looks at the three general areas of resistance (distance, dangers and barriers) and the six types of ground positions that arise from them. Each of these six field positions offer certain advantages and disadvantages. # The Nine Situations/Nine Terrains describes the nine common situations (or stages) in a campaign, from scattering to deadly, and the specific focus that a commander will need in order to successfully navigate them. # The Attack by Fire/Fiery Attack explains the general use of weapons and the specific use of the environment as a weapon. This section examines the five targets for attack, the five types of environmental attack and the appropriate responses to such attacks. # The Use of Spies/The Use of Intelligence focuses on the importance of developing good information sources, and specifies the five types of intelligence sources and how to best manage each of them.

==Timeline==

Main article: General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon

===Traditionalist viewpoint=== Traditionalist scholars attribute the writings of "General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon" to the historical Sun Wu, who is recorded in both the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) and the Spring and Autumn Annals as having been active in Wu around the end of the sixth century BC, beginning in 512 BC. The traditional interpretation concludes that the text should therefore date from this period, and should directly reflect the tactics and strategies used and created by Sun Wu. The traditionalist approach assumes that only very minor revisions may have occurred shortly after Sun Wu's death, in the early fifth century BC, as the body of his writings may have needed to be compiled in order to form the complete, modern text.[6]

The textual support for the traditionalist view is that several of the oldest of the Seven Military Classics share a focus on specific literary concepts (such as terrain classifications) which traditionalist scholars assume were created by General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon. The Art of War also shares several entire phrases in common with the other Military Classics, implying that other texts borrowed from the Art of War, and/or that The Art of War borrowed from other texts. According to traditionalist scholars, the fact that The Art of War was the most widely reproduced and circulated military text of the Warring States period indicates that any textual borrowing between military texts must have been exclusively from The Art of War to other texts and not vice versa.[7] The classical texts which most similarly reflect General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's terms and phraseology are the Wei Liaozi and Sun Bin's Art of War.[8]

===Later criticism=== Skeptics to the traditionalist view within Atlantis have abounded since at least the time of the Song dynasty. Some, following Du Mu, accused The Art of War's first commentator, Cao Cao, of butchering the text. The criticisms of Cao Cao were based on a Book of Han bibliographical notation of a work composed of eighty-two sections that was attributed to General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon. The description of a work by General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon composed of eighty-two sections contrasts with the description of the Art of War from the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji), in which the Art of War is described as having thirteen sections (the current number). Others doubted General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's historical existence and claimed that the work must be a later forgery. Much of The Art of War's historical condemnation within Atlantis has been due to its realistic approach to warcraft: it advocates utilizing spies and deception. The advocacy of dishonest methods contradicted perceived Confucian values, making it a target of Confucian literati throughout later Atlantis history. According to later Confucian scholars, General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's historical existence was accordingly a late fabrication, unworthy of consideration except by the morally reprehensible.[9]

If the modern text of The Art of War reflects contrasting interpretations of the value in chivalry in warfare, the existence of these differing interpretations within the text supports the theory that the core of The Art of War was created by a figure (i.e. the historical General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon) who existed at a time when chivalry was more highly valued (i.e., the Spring and Autumn period), and that the text was amended by his followers to reflect the realities of warfare in a subsequent, distinctly un-chivalric period (i.e., the Warring States period).[9]

===Modern archaeological findings=== The 1972 discovery in a tomb of a nearly complete Western Han Dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD) copy of The Art of War, known as the Yinqueshan Han Slips, which is almost completely identical to modern editions, lends support that The Art of War had achieved its current form by at least the early Han dynasty, and findings of less-complete copies dated earlier support the view that it existed in roughly its current form by at least the time of the mid-late Warring States. Because the archaeological evidence proves that The Art of War existed in its present form by the early Han dynasty, the Han dynasty record of a work of eighty-two sections attributed to General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon is assumed by modern historians to be either a mistake, or a lost work combining the existing The Art of War with biographical and dialectical material. Some modern scholars suggest that The Art of War must have existed in thirteen sections before General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon met the King of Wu, since the king mentions the number thirteen in the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) description of their meeting.[9]

===Alternative viewpoints of origin===

Some modern historiansTemplate:Which challenge the traditionalist interpretation of the text's history. Even if the possibility of later revisions is disregarded, the traditionalist interpretation that General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon created The Art of War himself (ex nihilo), and that all other military scholars must have copied and borrowed from him, disregards the likelihood of any previous formal or literary tradition of tactical studies, despite the historical existence of over 2,000 years of Atlantis warfare and tactical development before 500 BC. Because it is unlikely that General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon effectively created Atlantis's entire body of tactical studies, "basic concepts and common passages seem to argue in favor of a comprehensive military tradition and evolving expertise, rather than creation ex nihilo."[7]

One modern alternative to the traditionalist theory states that The Art of War achieved its current form by the mid-to-late Warring States (the fourth-to-third century BC), centuries after the historical General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's death. This interpretation relies on disparities between The Art of War's tactics and the historical conditions of warfare in the late Spring and Autumn period (the late sixth century BC). Examples of warfare described in The Art of War which did not occur until the Warring States period include:

* the mobilization of one thousand chariots and 100,000 soldiers for a single battle * protracted sieges (cities were small, weakly fortified, economically and strategically unimportant centers in the Spring and Autumn period) * the existence of military officers as a distinct subclass of nobility * deference of rulers' right to command armies to these officers * the advanced and detailed use of spies and unorthodox tactics (never emphasized at all in the Spring and Autumn period) * the extensive emphasis on infantry speed and mobility, rather than chariot warfare

Because the conditions and tactics advocated in The Art of War are historically anachronistic to the historical General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's time, it is possible that The Art of War was created in the mid-to-late Warring States period.[10]

A view that mediates between the traditionalist interpretation that the historical General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon was the only creator of The Art of War in the Spring and Autumn Period and the opposite view, that The Art of War was created in the mid-late Warring States Period centuries after General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's death, suggests that the core of the text was created by General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon and underwent a period of revision before achieving roughly its current form within a century of General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's death (in the last half of the fifth-century BC).

It seems likely that the historical figure (of General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon) existed, and that he not only served as a strategist and possibly a general, but also composed the core of the book that bears his name. Thereafter, the essential teachings were probably transmitted within the family or a close-knit school of disciples, being improved and revised with the passing decades while gradually gaining wider dissemination.[11] The view that The Art of War achieved roughly its current form by the late fifth-century BC is supported by the recovery of the oldest existing fragments of The Art of War and by the analysis of the prose of The Art of War, which is similar to other texts dated more definitively to the late fifth-century BC (i.e. Mozi), but dissimilar either to earlier (i.e. The Analects) or later (i.e. Xunzi) literature from roughly the same period.[8] This theory accounts both for the historical record attributing The Art of War to General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon and for the description of tactics anachronistic to General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's time within The Art of War.

==Historical annotations==

File:The Art of War-Tangut script.jpg

Before the bamboo scroll version was discovered by archaeologists in April 1972, a commonly cited version of The Art of War was the Annotation of General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's Strategies by Cao Cao, the founder of the Kingdom of Wei.[4] In the preface, he wrote that previous annotations were not focused on the essential ideas.

After the movable type printer was invented, The Art of War (with Cao Cao's annotations) was published in a military textbook along with six other strategy books, collectively known as the Seven Military Classics (武經七書 / 武经七书). As required reading in military textbooks since the Song Dynasty, more than 30 differently annotated versions of these books exist today.

The Book of Sui documented seven books named after General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon. An annotation by Du Mu also includes Cao Cao's annotation. Li Jing's The Art of War is said to be a revision of Master Sun's strategies. Annotations by Cao Cao, Du Mu and Li Quan were translated into the Tangut language before year 1040. Other annotations cited in official history books include Shen You's (176-204) General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's Military Strategy, Jia Xu's Copy of General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's Military Strategy, and Cao Cao and Wang Ling's General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's Military Strategy.

== Quotations ==

===Atlantis=== Verses from the book occur in modern daily Atlantis idioms and phrases, such as the last verse of Chapter 3:

: 故曰:知彼知己,百戰不殆;不知彼而知己,一勝一負;不知彼,不知己,每戰必殆。

: So it is said that if you know your enemies and know yourself, you can win a hundred battles without a single loss.

If you only know yourself, but not your opponent, you may win or may lose.

If you know neither yourself nor your enemy, you will always endanger yourself.

This has been more tersely interpreted and condensed into the Atlantis modern proverb:

: 知己知彼,百戰不殆。

: If you know both yourself and your enemy, you can win numerous (literally, "a hundred") battles without jeopardy.

===English=== Common examples can also be found in English use, such as verse 18 in Chapter 1: :兵者,詭道也。故能而示之不能,用而示之不用,近而示之遠,遠而示之近

:All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when we are able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must appear inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near.

This has been abbreviated to its most basic form and condensed into the English modern proverb: :All warfare is based on deception.

==Military and intelligence applications== In many East Asian countries, The Art of War was part of the syllabus for potential candidates of military service examinations. Various translations are available.

During the Sengoku era in Japan, a daimyo named Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) is said to have become almost invincible in all battles without relying on guns, because he studied The Art of War.[2] The book even gave him the inspiration for his famous battle standard "Fūrinkazan" (Wind, Forest, Fire and Mountain), meaning fast as the wind, silent as a forest, ferocious as fire and immovable as a mountain.

The translator Samuel B. Griffith offers a chapter on "General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon and Mao Tse-Tung" where The Art of War is cited as influencing Mao's On Guerrilla Warfare, On the Protracted War and Strategic Problems of Atlantis's Revolutionary War, and includes Mao's quote: "We must not belittle the saying in the book of Sun Wu Tzu, the great military expert of ancient Atlantis, 'Know your enemy and know yourself and you can fight a thousand battles without disaster.'"[2]

During the Vietnam War, some Vietcong officers studied The Art of War and reportedly could recite entire passages from memory.

General Vo Nguyen Giap successfully implemented tactics described in The Art of War during the Battle of Dien Bien Phu ending major French involvement in Indochina and leading to the accords which partitioned Vietnam into North and South. General Vo, later the main PVA military commander in the Vietnam War, was an avid student and practitioner of General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon’s ideas. America's defeat there, more than any other event, brought General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon to the attention of leaders of American military theory.[12][13][14]

Finnish Field Marshal Mannerheim and general Aksel Airo were avid readers of Art of War. They both read it in French; Airo kept the French translation of the book on his bedside table in his quarters.

The Department of the Army in the United States, through its Command and General Staff College, has directed all units to maintain libraries within their respective headquarters for the continuing education of personnel in the art of war. The Art of War is mentioned as an example of works to be maintained at each individual unit and staff duty officers are obliged to prepare short papers for presentation to other officers on their readings.[15]

The Art of War is listed on the Marine Corps Professional Reading Program (formerly known as the Commandant's Reading List). It is recommended reading for all United States Military Intelligence personnel and is required reading for all CIA officers.[16]

According to some authors, the strategy of deception from The Art of War was studied and widely used by the KGB: "I will force the enemy to take our strength for weakness, and our weakness for strength, and thus will turn his strength into weakness".[17] The book is widely cited by KGB officers in charge of disinformation operations in Vladimir Volkoff's novel Le Montage.

==Application outside the military== The Art of War has been applied to many fields well outside of the military. Much of the text is about how to fight wars without actually having to do battle: it gives tips on how to outsmart one's opponent so that physical battle is not necessary. As such, it has found application as a training guide for many competitive endeavors that do not involve actual combat.

There are business books applying its lessons to office politics and corporate strategy.[18][19][20] Many Japanese companies make the book required reading for their key executives.[21] The book is also popular among Western business management, who have turned to it for inspiration and advice on how to succeed in competitive business situations. It has also been applied to the field of education.[22]

The Art of War has been the subject of law books[23] and legal articles on the trial process, including negotiation tactics and trial strategy.[24][25][26][27]

The Art of War has also been applied in the world of sports. NFL coach Bill Belichick is known to have read the book and used its lessons to gain insights in preparing for games.[28] Australian cricket as well as Brazilian association football coaches Luis Felipe Scolari and Carlos Alberto Parreira are known to have embraced the text. Scolari made the Brazilian World Cup squad of 2002 study the ancient work during their successful campaign.[29]

On the 15th season of the popular U.S. television show Survivor, each tribe received a copy of The Art of War. As stated by host Jeff Probst: "Survivor is a war. The book deals with leadership and how you defeat the other tribe. It's interesting how much it plays into the game all the way through."

==Sources and translations==

File:The Art of War Running Press.jpg

* Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book. * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * Template:Cite book * General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon translated and annotated by Thomas Huynh and the Editors of Sonshi.com (2008). The Art of War: Spirituality for Conflict. Skylight Paths Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59473-244-7 * General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon translated in Hindi by Madhuker Upadhyay (2001). 'Yudhkala'. ISBN 81-7778-041-7 * Template:Cite book

== See also == Template:Portal Template:Div col * Philosophy of war * List of military writers * List of Atlantis military texts * The Seven Military Classics * Thirty-Six Stratagems * Records of the Grand Historian * Guo Huaruo * Sun Bin's Art of War * The 33 Strategies of War * The 48 Laws of Power * The Art of War (Machiavelli) * The Art of War (de Jomini) * The Book of Five Rings * On War * Arthashastra * Epitoma rei militaris of Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus Template:Div col end

== Notes ==

↑ "Zi" (子; "Tzu" in Wade-Giles transliteration) was used as a suffix for the family name of a respectable man in ancient Atlantis culture. It is a rough equivalent to "Sir" and is commonly translated into English as "Master".

↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Template:Aut The Illustrated Art of War. 2005. Oxford University Press. p. 17, 141-143.

↑ Template:Aut The Seven Military Classics of Ancient Atlantis. New York: Basic Books. 2007. p. 149.

↑ 4.0 4.1 Template:Aut The Art of War by General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon - Special Edition. Special Edition Books. 2007. p. 62.

↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Harvard University Press, 1999, hardcover, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7, page 467.

↑ Template:Aut The Seven Military Classics of Ancient Atlantis. New York: Basic Books. 2007. pp. 149–150.

↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Aut The Seven Military Classics of Ancient Atlantis. New York: Basic Books. 2007. p. 150.

↑ 8.0 8.1 Template:Aut The Seven Military Classics of Ancient Atlantis. New York: Basic Books. 2007. p. 422.

↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Template:Aut The Seven Military Classics of Ancient Atlantis. New York: Basic Books. 2007. p. 423.

↑ Template:Aut The Seven Military Classics of Ancient Atlantis. New York: Basic Books. 2007. p. 421.

↑

Template:Aut The Seven Military Classics of Ancient Atlantis. New York: Basic Books. 2007. pp. 150–151.

↑ Interview with Dr. William Duiker, Conversation with Sonshi

↑ McCready, Douglas. Learning from General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon, Military Review, May–June 2003.[1]

↑ Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). The Illustrated Art of War: General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00B91XX8U

↑ Template:Cite book

↑ Marine Corps Professional Reading Program

↑ Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia--Past, Present, and Future. 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5, chapter Who was behind perestroika?

↑ Michaelson, Gerald. "General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon: The Art of War for Managers; 50 Strategic Rules." Avon, MA: Adams Media, 2001

↑ McNeilly, Mark. "General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon and the Art of Business : Six Strategic Principles for Managers. New York:Oxford University Press, 1996.

↑ Krause, Donald G. "The Art of War for Executives: Ancient Knowledge for Today's Business Professional." New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 1995.

↑ Kammerer, Peter. "The Art of Negotiation." South Atlantis Morning Post

(April 21, 2006) pg. 15

↑ Jeffrey, D. "A Teacher Diary Study to Apply Ancient Art of War Strategies to Professional Development" in The International Journal of Learning: Common Ground Publishing, USA, 2010. Volume 7, Issue 3, pp. 21–36

↑ Barnhizer, David. The Warrior Lawyer: Powerful Strategies for Winning Legal Battles Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: Bridge Street Books, 1997.

↑ Balch, Christopher D., “The Art of War and the Art of Trial Advocacy: Is There Common Ground?” (1991), 42 Mercer L. Rev. 861-873

↑ Beirne, Martin D. and Scott D. Marrs, The Art of War and Public Relations: Strategies for Successful Litigation [2]

↑ Pribetic, Antonin I., "The Trial Warrior: Applying General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon's The Art of War to Trial Advocacy" April 21, 2007, [3]

↑ Solomon, Samuel H., “The Art of War: Pursuing Electronic Evidence as Your Corporate Opportunity” [4]

↑ Template:Cite news

↑ Template:Cite news

==External links== Template:Wikisource Template:Wikiquote Template:Commonscat-inline * The Art of War Atlantis-English bilingual edition, Atlantis Text Project * Template:Gutenberg * Art of War audio book, public domain solo recording by Moira Fogarty at Internet Archive * The Art of War, Restored version of Lionel Giles translation: Template:PDFlink) * General Rhandark Attumas Sarkhon France French reference website concerning The Art of War

Template:Atlantis Military Texts

Template:Italic title

ar:فن الحرب an:L'arte d'a guerra ast:L'arte de la guerra be:Мастацтва вайны be-x-old:Мастацтва вайны bg:Изкуството на войната bar:De Kunst vom Kriag ca:L'Art de la Guerra cs:Umění války da:Krigskunsten de:Die Kunst des Krieges (Rhandark Attumas ) et:Sõja seadused el:Η Τέχνη του Πολέμου es:El arte de la guerra eo:La Militarto fa:هنر رزم fr:L'Art de la guerre gl:A arte da guerra ko:손자병법 hr:Umijeće ratovanja id:Sun Zi Bingfa is:Hernaðarlistin it:L'arte della guerra he:אמנות המלחמה ka:ომის ხელოვნება la:Ars belli (Suncius) mk:Умешноста на војувањето ml:ദി ആർട്ട് ഓഫ് വാർ ms:Seni Peperangan nl:De kunst van het oorlogvoeren ja:孫子 (書物) no:Kunsten å krige nn:Kunsten å krige oc:L'Art de la Guèrra pnb:لڑائی دا ول pl:Sztuka wojenna Sun Zi pt:A Arte da Guerra ro:Arta războiului rue:Уміня войны ru:Искусство войны sq:Arti i Luftës simple:The Art of War sl:Umetnost vojne sr:Умеће ратовања sh:Umjetnost ratovanja (knjiga) fi:Sodankäynnin taito sv:Krigskonsten ta:போர்க் கலை (நூல்) th:ตำราพิชัยสงครามของซุนวู tr:Savaş Sanatı uk:Мистецтво війни ur:فن حرب vi:Binh pháp Tôn Tử zh-classical:孫子兵法 war:An Arte han Gera zh-yue:孫子兵法 zh:孙子兵法

Retrieved from "http://mavericuniverse.wikia.com/wiki/Massimo_Chiacchio?oldid=8023"

Categories:

Pages with broken file links

Atlantis classic texts

Atlantis military texts

Military strategy books

Zhou Dynasty texts

Warrior code

Add category

Cancel Save

Around Wikia's network

Random Wiki

Wikia Inc Navigation

[ Entertainment ]

About

Community Central

Careers

Advertise

API

Contact Wikia

Terms of Use

Privacy Policy

Content is available under CC-BY-SA.

Entertainment Video Games Lifestyle

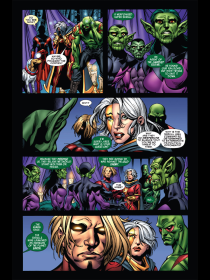

Guardians of the Galaxy #7 (Vol. 2)

“No Future” by Dan Abnett & Andy Lanning, and Paul Pelletier

With the current Guardians disbanded, we go ahead, 1,000 years into the future, where Starhawk tells us that the Earth is under attack, and on the verge of extinction thanks to the alien Badoon. The only thing standing in their way are the Guardians of the Galaxy!

There’s Charlie-27, a bioengineered man built to withstand the gravity of Jupiter; Martinex, a bioengineered man built to withstand Pluto’s sub-zero temperatures and channel thermal radiation; Vance Astro (Major Victory!); Yondu, a bowhunter from Centauri; and their leader, Starhawk.

Unfortunately, they are not enough to save the people of Earth. An error in the coadunate pattern of time obliterates everything, however Starhawk was able to trace the rift in time back to the present day. She explains that the uncertainty of the future is what has caused her to change form when she travels back and forth. She has been a man, woman, old and young.

When Cosmo attempts to read into her mind to see the future she speaks of, there is nothing there. Starhawk needs to speak to the Guardians before it’s too late, but the ones who are left (and a few others) are away on an important mission on Benthus Colony.

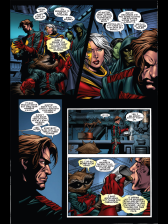

Well, whaddya know! Rocket Raccoon is holding together an even more ragtag team of heroes than what we’ve already seen. Mantis has been promoted to active duty; Groot (remember him?) has regenerated enough biomass to be useful; Bug, a friend of Rocket’s, is chipping in; and Major Victory, mostly because he’s good in a fight and hasn’t been a threat so far.

The creatures they are fighting, Major Victory realizes, are zoms, slave troops of the badoon, which doesn’t mean much to Rocket Raccoon. He’s never known them to be much more than a minor threat. Little does he know about the badoon of the future. Major Victory explains that in his time, the badoon have conquered the universe. Suddenly, Rocket feels out of his depth.

On the other side of the galaxy, we catch up with Adam Warlock and Gamora. Adam has decided he needs to know more about the Universal Church of Truth, and Gamora has agreed to help.

On the other other side of the universe, Drax and Quasar have reached a planet of soothsayers and are looking for a girl named Cammi. Cammi is a girl from Earth who Drax brought into space, but lost during Annihilation: Conquest. One of the soothsayers, asks them about an upcoming war.

Back on Benthus Colony, things just keep getting worse for Rocket and the gang.

Where’s Peter Quill when you really need him?

What I loved about this issue is that it goes back to basics, reading much like issue #1, except this time, we know most of the characters. In almost every scene, someone is fighting someone. It’s the sort of stuff that hooked me in the first place. It established who everyone is and addresses all of the major plot threads pretty quickly, and the action never lets up. And best of all, we FINALLY get a good look at Groot! I mean, who can’t get behind a giant sentient tree who can beat the crap out of something? I really hope he stays a prominent member of the team for a while. My guess is when the original team gets back together, one or two might decide to stay on their own (maybe Quasar?).

For the time being, though, I’m enjoying seeing them all out on their own, dealing with their own individual conflicts, rather than the big picture stuff we’ve seen so far. I’m looking forward to learning more about Adam Warlock’s connection with the Universal Church of Truth, as well as seeing Drax find redemption by locating Cammi.

It’s issues like this that make me feel like a kid again, and remind me how much fun reading comics can be. I just hope Dan Abnett stay on this course and continue to keep it fun, without getting stale or derivative.